“We have really great funding for small undergraduate projects,” Goodell cites as one reason the Newark campus is a uniquely advantageous place to start research. “I’ve had the pleasure of seeing some of my Newark students develop their own research projects, obtain funding and complete a thesis.” Though science majors typically move to the Columbus campus after a year or two, Goodell feels that students who start research projects at the Newark campus are more competitive for research positions and fellowships once they transition to the Columbus campus.

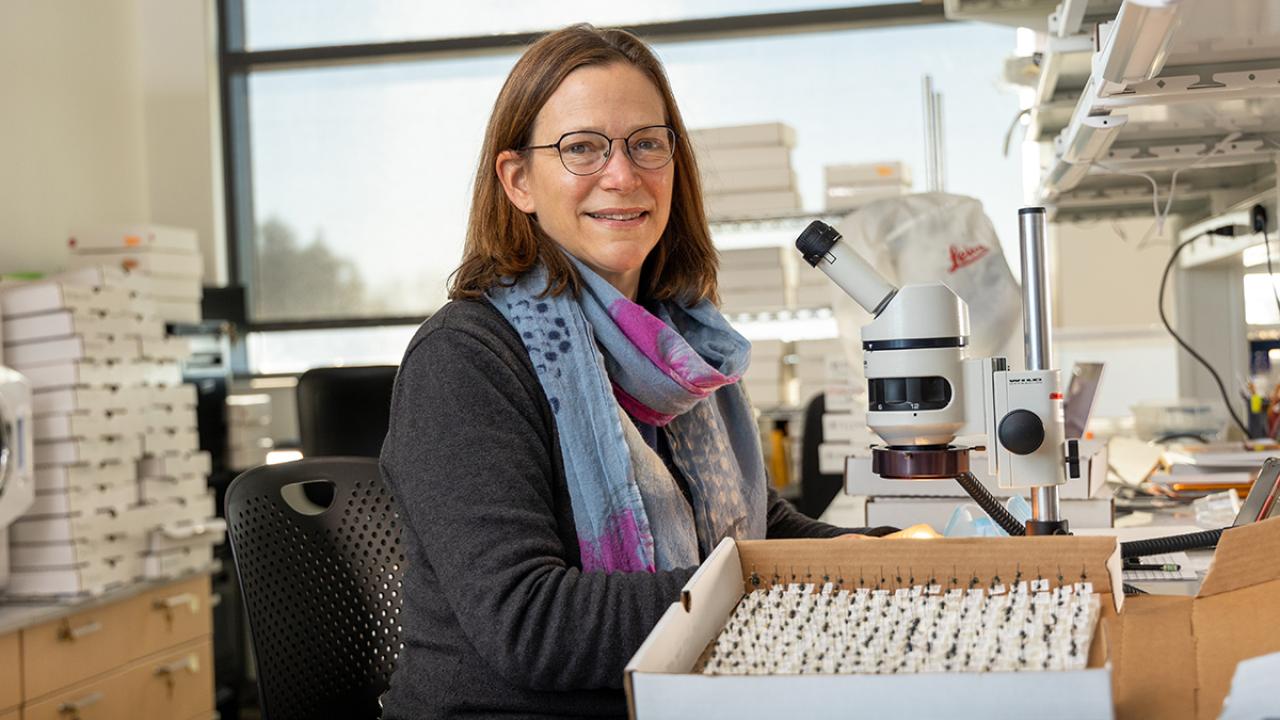

Since 2004, Goodell has taught undergraduates at the Newark campus and led graduate research on both Newark and Columbus campuses. Her research focuses on the ecology and conservation of pollinators, especially of native bees.

Goodell’s interest in pollinators was piqued during her master’s research on the genetics and evolution of plants. She realized the pivotal role pollinators played in the mating patterns of plants. When she moved to SUNY Stony Brook to complete her doctorate, Goodell interacted with a vibrant community of bee biologists. She met renowned bee biologist Jerome G. Rozen, PhD, then curator of the Hymenoptera collection at the American Museum of Natural History, who fostered her interest in bee ecology.

“He was so kind and generous with his time,” she said. “He helped me obtain a pass to the collections. I spent every Friday in Manhattan at the museum. I’d show up in his lab, and he would give me little challenges, such as a new bee to identify. He taught me so much about taxonomy, that I was able to identify the species of bees that I found in the field.”

Goodell acts as a similar figure to her students at Ohio State Newark. “I teach a lot of freshmen. Many of them are undecided about their careers. It’s a really wonderful time to meet a student because you can have an impact on the trajectory of their career,” she explained.